The anchor of the Kanrin Maru?

Weblog

With the information brought to us by Mr. Yoshida in our last blog post, we finally come to discussing the alleged anchor of the Kanrin Maru.

At that point we had yet to see this anchor for ourselves, so we were looking forward to seeing it in the flesh (or iron, that is). Mr. Kimoto, pretty much being our guide and a great reader of minds, had prepared for us a visit to the Kikonai Town Museum, where we found the anchor of the Kanrin Maru in all its splendour. Exhibited on a pebble-filled square, lit under the atrium lights of the museum, the iron anchor was obviously bombarded as the museum’s top piece.

But how did the anchor get here? And how does one find an anchor in the first place? Well, apparently the anchor was hauled up by a fishing boat in 1984. Fishermen quite often haul up artefacts of all kinds, as these objects tend to get snagged by the fishing equipment, especially when using nets. This is one of the reasons fishermen are a vital source in finding your shipwreck. Before we visited Kikonai, all that was known to us thus far came from a newspaper article stating that it was hauled up from a depth of 22 metres approximately 2 km off the coast. No information was given about where it was found. However, right on the first day of our visit we were told that the location of the anchor is in fact known now, as it was found near Saraki Misaki and that it actually came from a depth of 32 metres.

So, is there any basis to believe that this anchor could actually belong to the Kanrin Maru? We approached this question with caution. For anchors were often lost at sea when cables (either of rope or chain) snapped under sheer strain, e.g. when holding out in a storm or simply when getting stuck, exceeding the holding power in the process. So it is not that much of a surprise to find an anchor in the first place, while it furthermore does not automatically indicate that there is a shipwreck nearby.

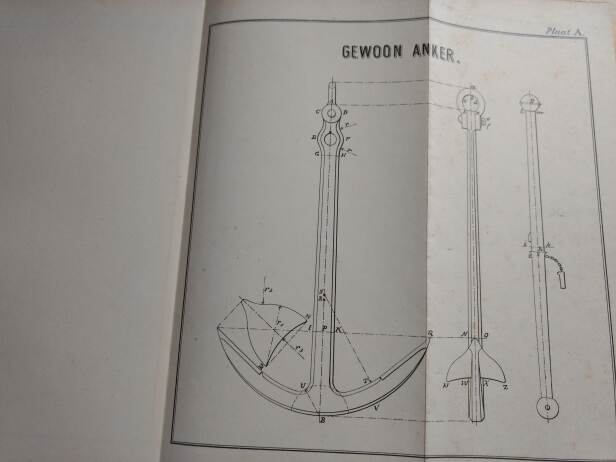

Its characteristics however, may tell us a bit more. Soon we learned that the long, central, pillar-like part called the shank is about 2.82 metres long, the stock measures 2.75 metres wide, while its so-called arms with the flukes and bills (together forming the pointy ends of the arms) measure 2 metres wide, from end to end. Judging from its shape, this is what the British Navy would call the Admiralty Pattern stock-anchor, which the Dutch Navy at the time called the Common Anchor (‘gewone anker’ in Dutch). As the name suggests, this represents quite a common anchor form (pretty much like the ones you'll find tattoeed on someone's arm).

An important feature on this particular anchor is its iron stock, which is the wide bar, folded on one end, situated near the top of the shank. From George Cotsell’s Treatise on Ships’ Anchors (1856) and others, we learn that the British Navy started introducing iron-stocked anchors in the 19th century, slowly replacing anchors with wooden stocks. In the first half of the 19th century, especially anchors with weights below 1500 kg were equipped with iron stocks, while the feature also came in vogue for bigger anchors from the 1840s onwards with the arrival of steamer warships. In the 19th century, the Dutch Navy closely followed the trend of the British. In an 1844 issue of the journal ‘Tijdschrift toegewijd aan het zeewezen’ the Dutch Navy shared new regulations regarding the anchors of Dutch warships: from that point on all anchors of 1300 kilograms and lighter were to be equipped with iron stocks. Later, all the common anchors of the Dutch Navy were to be equipped with iron stocks, while during the latter part of the 19th century stockless anchors slowly started to take centre stage up to the point where the Navy practically dropped the use of iron-stocked anchors completely.

At this point it is uncertain whether anchors such as these could have been equipped on Japanese vessels other than 19th century warships, as the predominant Japanese anchor is a four-armed anchor like the one briefly discussed in the previous blog post. However, it seems that the common anchor also remained in use on European and American private vessels after the 19th century as well. This would place the ‘Kikonai anchor’ at the earliest in the 19th century, and more likely somewhere between the 1850s and 1900, after the opening of Japan and the increase of foreign-style ships traversing Japanese waters.

So, is there any information known about the anchors equipped on the Kanrin Maru? Well for this we turn to the City Archives of Rotterdam where we found the archives of the ‘Nederlandse Stoomboot Maatschappij’ [Dutch Steamboat Company] – this company was not only responsible for the steam machinery and kettles of the Kanrin Maru, but also directed the overall construction of the vessel, with Fop Smit’s shipyard in Kinderdijk being the sub-contractor to deliver the wooden hull of the ship. The Steamboat Company’s well-kept books reveal that it commissioned the Koninklijke Nederlandsche Grofsmederij in Leiden [Royal Dutch Metal Factory] to deliver five anchors and two cable chains. This metal factory was also the main supplier of anchors and the like for the Dutch Navy, while the Dutch Navy was in turn closely involved in the construction of the Kanrin Maru.

The heaviest anchor on the order list weighed 800 kg. Now, apparently the anchor found near Kikonai weighs around 1000 kg. This would leave us with a difference of 200 kg, which would suggest that the ‘Kikonai anchor’ is not the Kanrin Maru’s original anchor. However, one hypothesis that is still being considered is that the anchor weights mentioned on the order list do not include the weight of iron stocks, as there is in fact no mention of this. At a first glance, leaving out the weight of the iron stock would perhaps not make much sense, as the additional weight would add to the overall holding power of an anchor. While the hypothesis is still under scrutiny *Update - [13-01-2018] an 1858 document clearly states this is the case* , we did find official documents that seem to support said hypothesis.

One of the main arguments supporting this idea comes from a number of 19th century official regulations regarding weights and measurements agreed upon between the Dutch Navy and the Koninklijke Nederlandse Grofsmederij. In these regulations it is clearly stated that the weights of the common anchors listed in these documents did not include the weights of iron stocks. A reason for leaving out the stock weights could be based partly on the iron stocks not contributing to the strength of the anchor itself.

But how much would the iron stock add to the weight of the anchor, you ask? Well, according to the Dutch Navy regulations, the weight of the iron stock was set at approximately 25% of the anchor’s weight. For the 800 kg anchor of the Kanrin Maru that would mean a stock of 200 kg. Add that up and you have 1000 kg; a perfect match in weight with the 'Kikonai anchor'. Still, if this hypothesis is indeed correct, this would only allow us to conclude that there is a match in weight, but that this still does not provide enough evidence for a definitive conclusion.

*Update - [13-01-2018]*

A document dating from 1858 containing the regulations regarding anchors and the like as agreed upon between the Dutch Navy and the Koninklijke Nederlandse Grofsmederij, shows three different anchor designs. Depicted in the centre is Cotsell's improved Admiralty anchor at the time in use by the British Navy. To the left and right of Cotsell's design are depicted the new and and old iron-stock anchor designs in use by the Dutch Navy. From these drawings, it clearly shows that the shank and arms of the Dutch anchors were angular, while Cotsell's design has a rather rounded shank and ditto arms. Cotsell's design strikingly matches the 'Kikonai anchor'. Now, even though the 'Kikonai anchor' seems to perfectly match the total weight of the heaviest of the original anchors equipped on the Kanrin Maru, with our current findings it seems to be more likely that the 'Kikonai anchor' is not a Dutch Navy anchor, but rather an admiralty anchor. Still, there is a chance that this 'Kikonai anchor' was the replacement for the original, but finding evidence to back this up would be very difficult and near impossible. More comparitive research is required.

To make it even more difficult, other vessels are known to have wrecked in the vicinity of Saraki Misaki. One of which was a Russian vessel that wrecked in 1901, which could well have been equipped with an anchor such as the 'Kikonai Anchor'. Also, while the anchor matches the weight of the heaviest anchor originally equipped on the Kanrin Maru, for all we know, the 'Kikonai Anchor' may have been the smaller anchor of a vessel larger than the Kanrin Maru. Would the anchor still have its maker’s mark, now that would make it a lot easier to learn about its origins. We do have witness accounts stating it was marked with the letters COP or CCP, and someone said he’d even noticed what seemed like Roman numerals. These supposed marks do not yet ring any bells though, and they most certainly do not match the initials 'K.N.G.' which are the initials known from the marks of the Koninklijke Nederlandse Grofsmederij.