Pottery on the Rooswijk

Weblog

Although it is often humble in appearance, pottery is usually incredibly informative. Specialists Jan van Doesburg (Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed) and Duncan Brown (Historic England) are currently analysing the pottery sherds found on the Rooswijk. In this blog by Alex Bliss and Duncan Brown, some of the pottery sherds will be discussed, showing how detailed analysis of sherds can provide further insights into the story of the ship and its crew.

Methods of study

Every pottery sherd has two characteristics that inform our analysis: fabric – i.e. the type of clay it is made from; and form – i.e. the shape of the sherd and type of pot it has come from. While the fabric tells us where and how a pot was made, the form demonstrates how a pot was used and when it was made. Additionally, decoration and style can reflect cultural influences, while external traces, such as soot or wear-marks, show if and how it was used.

Broadening our scope, we can also examine in what other archaeological contexts this pottery occurs. Such comparisons can inform us about the social use of different pottery types; for example, whether the use of a certain pottery type is widespread across a country, or rather restricted to specific households in a limited area. Finally, in case pottery is found which was made in a different country, we can identify networks of trade. The latter is especially helpful when we are seeking to understand how the economies of states and countries operated in the past. In the context of the Rooswijk, we can use these comparative methods and varying perspectives to address several questions: 1) what was the range of products and pottery vessel types on board; 2) how was pottery used on the ship and by whom; 3) how does the pottery from the Rooswijk compare with assemblages from other VOC ships, particularly within the context of the ‘Equipage’ or ship’s inventory?

Common pottery from the Netherlands and Germany

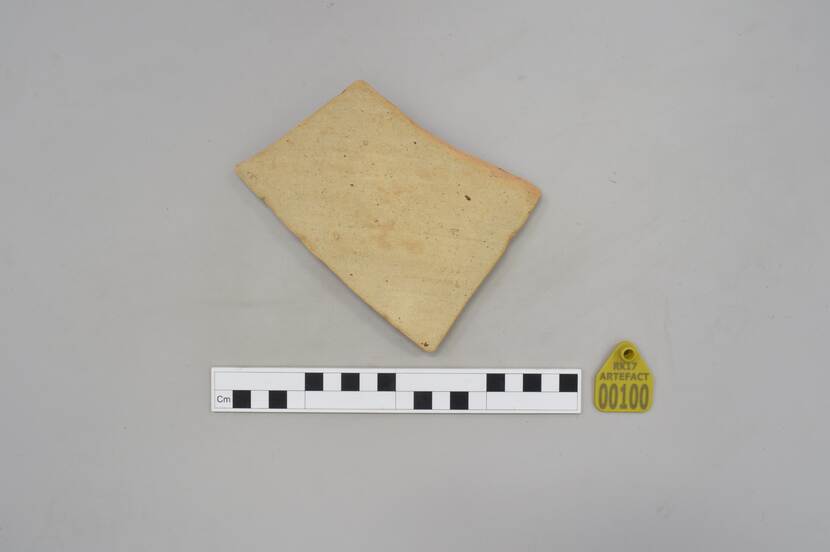

To date, we have investigated 43 fragments of pottery that were taken from the wreck-site in 2017 and 2018. It is very likely that this number will increase as we continue to de-concrete larger objects and concretions.

The pottery from Rooswijk compares well to that from other VOC shipwrecks, with Dutch and Rhenish stonewares making up the bulk of the assemblage. Dutch red earthenware, a common type produced at several locations around the Low Countries, took the form of skillets and small cauldron-type cooking pots – which were most likely used in the ship’s galley.

Rhenish stonewares comprise the largest proportion of the discovered Rooswijk pottery. From the 15th century onwards, these were produced in huge quantities at several centres around the Rhine and its tributaries. They are common finds on excavations in the Netherlands as well as on VOC shipwrecks. The largest group found on the Rooswijk are from Frechen and Westerwald in Germany. Pottery from Frechen usually has a brown, speckled salt glaze and mainly takes the form of narrow-necked jugs or bottles. A speciality of Frechen was the Bartmann (in English: bearded man) or Bellarmine jug. Pottery from Westerwald, more often occurring as tankards or jars, is usually grey with painted decoration in cobalt blue.

Spanish Olive-jars and Chinese tea sets

Although the Rooswijk’s ceramic assemblage is dominated by Dutch and Rhenish products, there are also some pieces from much further afield: fragments of the so-called bojita or ‘olive-jars’ from Seville and fragments of porcelain from China. Bojita’s are large storage vessels which were used for preserved fruit, including olives and olive oil. They probably would have been used by the ship’s cook and are often found in the assemblage of other VOC shipwrecks. The Chinese porcelain reflects the long distance connections that the VOC and others had established by the middle of the 18th century. Tea drinking had become very fashionable in the west and thousands of cups, saucers and teapots were imported at this time. Fragments, the rim of a cup and sherds of two saucers, were probably part of a tea set brought on board for use by the ship’s officers. One of the saucer sherds has been hand-decorated with a rather charming coastal scene, clearly depicting a fishing boat, house and several trees.

About the Rooswijk Project

The Rooswijk was a Dutch East India Company vessel which sank on the treacherous Goodwin Sands, off Kent, in January 1740. The ship was outward-bound for Batavia (modern-day Jakarta) with trade goods. The site is now protected by the Protection of Wrecks Act 1973 and all access is controlled by a licensing system administered by Historic England on behalf of the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. The ship’s remains lie at a depth of some 25 metres and are owned by the Dutch Government. The UK government is responsible for managing shipwrecks in British waters, therefore both countries work closely together to manage and protect the wreck site. The Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, RCE, (on behalf of the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture) and Historic England (on behalf of the Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport) are responsible for the joint management of the Rooswijk.

An archaeological survey of the site in 2016, undertaken by RCE and Historic England, showed that the wreck site was at high risk. As a result, a two-year excavation project began in 2017. Wrecks such as the Rooswijk are part of the shared cultural maritime heritage across Europe and it’s important that cultural heritage agencies are able to work together to ensure that sites like this are protected, researched, understood and appreciated by all. The #Rooswijk1740 project is funded and led by the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands (Ministry of Education, Science and Culture), in collaboration with project partner Historic England and UK-contractor MSDS Marine.