Glass artefacts from archaeological contexts on land are usually preserved in poor condition and heavily fragmented. However, when conditions of deposition are favourable this is often contrasted in marine deposits – where objects can be quickly protected through being covered over by sediments or concreted. In this blog post, we will look at the diverse types of glass artefact discovered on Rooswijk and how analysis of these can provide a literal ‘treasure trove’ of information.

Written up by Alex Bliss, Dr. Francesca Gherardi, Sarah Paynter and Kamil Prus on behalf of the #Rooswijk1740 project.

Glass Bottles

Part of Rooswijk’s cargo has been stored in glass bottles. Broadly two different types have been discovered: the onion bottle and the ‘case’ bottle. Before the early 17th century, it was common for alcohol to be shipped in wooden casks as glass bottles were fragile, expensive and ill-suited for shipping. Aside from being extremely bulky, wooden casks could also have a negative effect on the contents due to their not being entirely airtight.

The above issues were partly addressed during the 1630s by the co-operation of English ex-privateer Sir Kenhelm Digby and glassworks manager James Howell. Their experiments with different types of fuel and hotter furnaces resulted in the creation of a very solid, dark green glass that broke far less easily – effectively, they had invented the precursor to the modern wine bottle. With a rounded, bulbous base and elongated neck, these quickly became known as ‘onion’ bottles – and were produced in England from the 1650s onwards in incredibly large quantities (some estimate over 3 million per year). We can date onion bottles by their form, as over time the necks shortened and the bodies became even more bulbous. Though their popularity had begun to wane in favour of other bottle types by the time Rooswijk sank in 1740, it is evident that they continued to be used – both in Britain and the Netherlands. In addition to the onion bottles we also have a smaller number of what are termed ‘case’ bottles – named so because they were easily stackable in cases due to their rectangular form and short, stubby necks. By contrast with onion bottles, case bottles were far more fragile, hence the cases. These are found on a number of VOC wrecks, for example the Zeewijk which wrecked off the coast of Western Australia in 1728, but also other wrecks like the much earlier Scheurrak SO1, a grain trader from the end of the 16th century.

Onion bottle found on Rooswijk (RK17:00019)

Case bottle found on Rooswijk (RK17:000163)

Intrusive material

In addition to these bottles which can be attributed with certainty to the Rooswijk’s sinking in 1740, there are two later examples reflecting what archaeologists call ‘intrusive’ material. These were thrown overboard or were part of another ship disaster in the area and washed into the wreckage by tidal action. The first is a bottle of probable early to mid-19th century date (which may have been used for wine), and the second a much later embossed bottle in light blue glass. Writing on the sides identifies the latter as containing powdered fruit juice, manufactured by Foster and Clark co. of Maidstone. It can be dated much more tightly to somewhere between the late 1890s and c. 1910 as Foster and Clark transitioned to become a limited company (and were named as so) on bottles made after this year.

‘Mallet’ bottle (mid-19th century) (RK17:00030)

Case Bottle for powdered fruit juice (c. 1890s-1910) (RK17:00165)

Shipping and drinking liquor

We do not know yet what was being contained in the bottles sunk with Rooswijk, but evidence from contemporary newspaper advertisements of bottled alcohol suggest fortified wines as the most likely candidate - perhaps along with spirits such as rum, brandy and jenever. Indeed, case bottles are sometimes nicknamed as ‘Dutch gin or jenever bottles’ – referencing their origin and that of the spirit Jenever they contained. Over thirty onion bottles and at least ten case bottles in various stages of completeness (not counting the innumerable fragments of undiagnostic glass which cannot be attributed to either type) were excavated from Rooswijk in 2017 and 2018, a number of which retained their corks. One onion bottle remains totally complete, still sealed by its cork and retaining liquid inside. This may represent the original contents of the bottle, and as such will be investigated. Also notable is that some of the onion bottles retained traces of a white residue, revealed under scientific analysis to be Pine resin (sometimes called colophony). This substance would have been used to ensure the bottle was completely airtight to prevent oxidation – and subsequent ruin – of these liquors.

Image: © #Rooswijk1740 project

Cork in bottle (RK18:00081)

Image: © #Rooswijk1740 project

Remains of a high-status clear glass goblet (RK17:00055)

The remains of a high-status clear glass goblet were also found. Compositional analysis of this goblet reveals that it was manufactured in what is now the Czech Republic – this region being famed for its high-quality ‘Bohemia crystal’ that reached the peak of its output during the 17th and 18th centuries. It is likely that this goblet would have formed part of a set, perhaps a component of tableware belonging to the ship’s officers or captain.

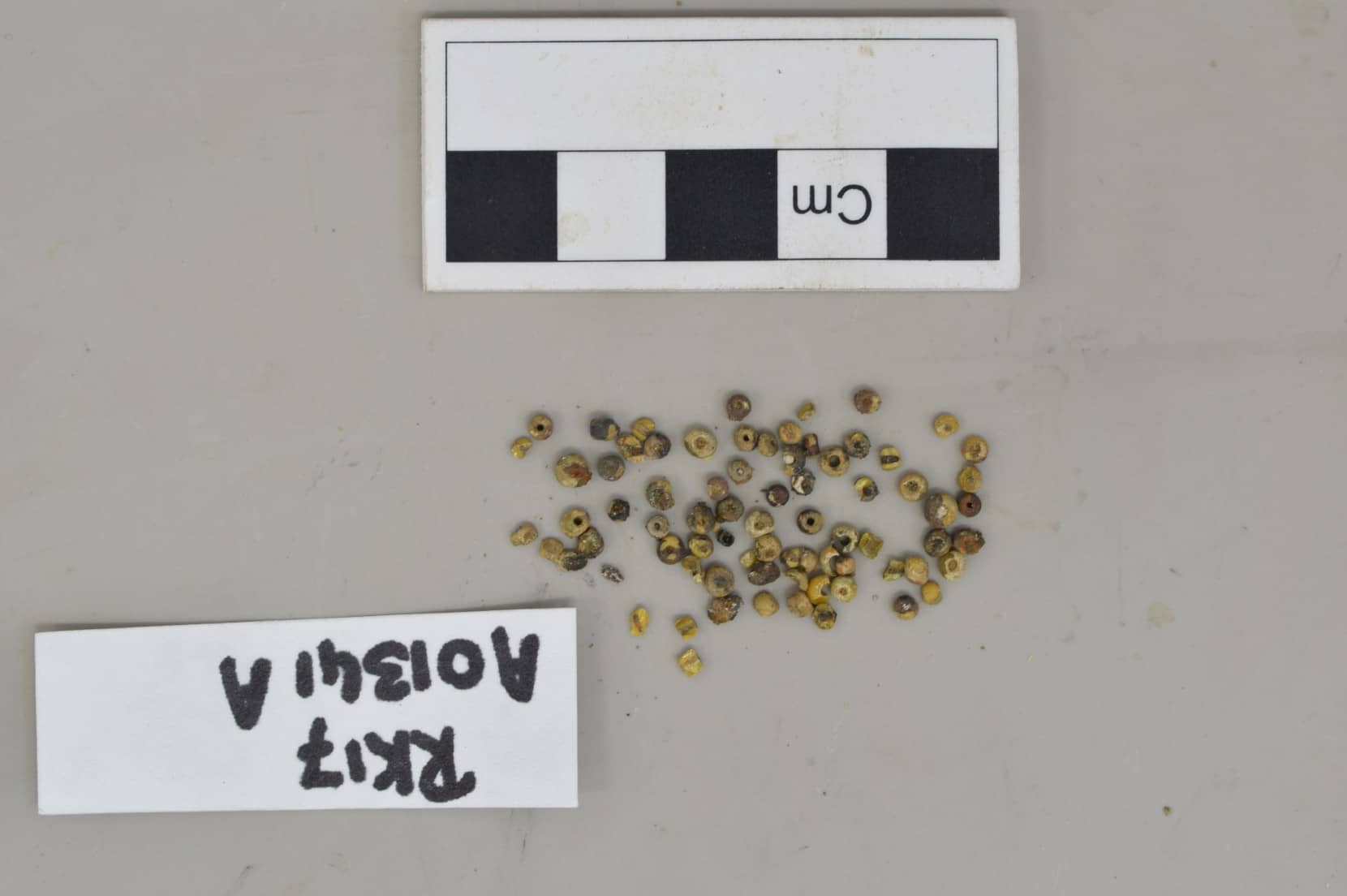

Glass beads

Moving away from bottles and drinking cups, we also have very large numbers of glass trade beads present within the Rooswijk assemblage. In some cases, these beads quite literally saturate the interiors of certain concretions – as can be seen on the X-ray image provided. Whereas most of these are very small examples in yellow, green and white glass we also have a single large ‘chevron’ bead, vividly coloured with red and blue stripes. The use of trade beads is most often connected with Africa, where they were exported in large numbers from the 16th century onwards as a form of currency. It is unclear why these were present on the ship in such numbers; are they an element of cargo, or personal trade by members of the crew as with some of the Rooswijk’s silver coins?

X-ray concretion (RK18 A00283)

Glass beads found on Rooswijk (RK17A01341A)

‘Chevron’ bead found on Rooswijk

The Rooswijk keeps on revealing its secrets to us. This continues while we are doing the conservation and analyses of the materials that we excavated in 2017 and 2018.

About the Rooswijk Project

The Rooswijk was a Dutch East India Company vessel which sank on the treacherous Goodwin Sands, off Kent, in January 1740. The ship was outward-bound for Batavia (modern-day Jakarta) with trade goods. The site is now protected by the Protection of Wrecks Act 1973 and all access is controlled by a licensing system administered by Historic England on behalf of the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. The ship’s remains lie at a depth of some 25 metres and are owned by the Dutch Government. The UK government is responsible for managing shipwrecks in British waters, therefore both countries work closely together to manage and protect the wreck site. The Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, RCE, (on behalf of the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture) and Historic England (on behalf of the Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport) are responsible for the joint management of the Rooswijk.

An archaeological survey of the site in 2016, undertaken by RCE and Historic England, showed that the wreck site was at high risk. As a result, a two-year excavation project began in 2017. Wrecks such as the Rooswijk are part of the shared cultural maritime heritage across Europe and it’s important that cultural heritage agencies are able to work together to ensure that sites like this are protected, researched, understood and appreciated by all. The project involves an international team led by RCE in partnership with Historic England. MSDS Marine are the UK Project Managers for the project.